Dead Companies Walking

Dead Companies Walking is a 2015 book by hedge fund manager Scott Fearon, written with Jesse Powell. It chronicles Scott Fearon's three decade career in investing, with a focus on his strategy of identifying and shorting the stocks of companies that are on the path to bankruptcy.

Scott started his own hedge fund on December 1, 1990, with roughly $3 million under management. A decade later, it was approaching $200 million.

In this book, Scott walks through many stories of his thoughts and what he was looking at with specific companies before he decided they were a worthy Short opportunity (or Long opportunity). Although he would crunch numbers and look at formulas, he seemed to place more emphasis on analyzing the management of the companies he was considering. Scott likes to personally meet with the CFO or CEO of the companies he’s looking into so he can get an inside take on what the management style and plans look like. He has personally met with over 2,000 company management teams including some of the highest profile CEO’s and CFO’s in the country.

Unlike the last few books I read about shorting fraud and scam companies, Scott Fearon is more focused on shorting real companies that just don’t have the right business model to keep their company moving in the right direction, and so Scott sees where the company is likely headed and wants to hop along for the ride down.

“Short-selling carries an infinite amount of risk. The most you can lose from buying a stock is its share price. Shorting a stock has no such floor. For that reason, short-sellers are almost always the smartest, the most savvy, and also the most cautious investors out there. If we weren’t, we’d all be broke. And contrary to popular opinion, we don’t target companies based on malic, and we don’t delight in the near ubiquity of failure in the business world. We simply acknowledge how common failure is and invest accordingly.” ~ Scott Fearon

From the book Introduction:

By Scott Fearson:

"Three types of businesses that falter and go under: frauds, fads, and failures. The frauds, like WorldCom and Enron, get most of the attention, because their stories are usually dramatic, full of intrigue and greed and deception. But frauds are an infinitesimal fraction of the number of companies that fail every year. Fads - companies or products that explode onto the scene before fizzling out are also relatively rare. Most companies that enter bankruptcy fall into the third category. They’re just plain old failures, the result of bad ideas, bad management, or a combination of the two.

As the manager of my hedge fund, I’ve shorted the stocks of over two hundred companies that have eventually gone bankrupt. Many of these businesses started out with promising, even inspired ideas. Others were once-thriving organizations trying to rebound from hard times. Despite their differences, they all failed because their leaders made one or more of six common mistakes that I look for:

- They learned only from the recent past.

- They relied too heavily on a formula for success.

- They misread or alienated their customers.

- They fell victim to a mania.

- They failed to adapt to tectonic shifts in their industry.

- They were physically or emotionally removed from their companies’ operation.

In my experience, the vast majority of people who fail in business are neither idiots for believing in their companies nor swindlers looking to dupe their customers and investors. All of the executives I am going to describe, even the ones who suffered the worst disasters, were intelligent, honest, and hard-working individuals. I have a great deal of respect for anyone who tries and fails in business, and I hope that when you finish this book, you will recognize just how ordinary, and important, failure is. It’s a critical part of what makes a healthy market economy – and it happens every day to some of the smartest people in the world.

Ideally, I don’t have to worry about covering my positions at all. That’s because, unlike most short-selling investors out there, I don’t seek out stocks I think are just going to dip a little bit in the near term. I look for genuine failures that seem destined for one outcome: bankruptcy and a zeroed-out stock price."

Chapter 1 - Historical Myopia

They learned only from the recent past.

Historical Myopia basically means shortsightedness in trying to understand the past. Scott Fearon dedicates this chapter to companies and management that he investigated and determined they were being too shortsighted when using the past as a factor in determining their future.

Global Marine (stock symbol GLM)

Global Marine owned a fleet of offshore drilling rigs and ships that it would lease out to oil companies. Just like every other energy related company in Texas in the early 80’s, Global Marine got very rich during the oil boom. In 1984 the stock was at a multi-year low but still held a considerable amount of great assets.

Scott and his partner at the time, Geoff, decided to meet with the CFO, a man named Jerry. This was Scott’s first ever meeting with a management team. When Scott asked the CFO, Jerry, about the low stock price, his response was: “ The oil business is cyclical in nature. We’re down for a little while and then we’re up again. Our drilling rigs leased out worldwide are currently at 70 percent. I’ve been in this business for decades and 70 percent is always the bottom. It never fails. Look, I’ll show you”.

He pulled a chart out and traced the up and down cycle of Global Marine’s “rig utilization rate” over the previous few decades. Every time it dipped below seventy, it turned around and shot up shortly after.

It was a classic winner according to the rules of value-investing. The share price was half the company’s book value. (book value = Assets minus Liabilities divided by the total Shares outstanding). Jerry’s presentation was very persuasive and most investors would see this as a prime opportunity. But Scott had two concerns: 1- He knew how risky it was to predict the bottom of a downturn (catching a falling knife), and 2- Jerry’s financial security depended on the company turning around, causing Jerry to have an unconscious bias in favor of Global Marine. Although Scott declined to invest in the company, he also decided not to short it either. That 70% utilization rate quickly dropped to 25%

“I can’t remember exactly how far back Jerry’s rig utilization chart stretched in time, but it wasn’t more than 20 years. Over that time span, Jerry was perfectly right: Global Marine’s utilization rate had never stayed below 70 percent for more than a quarter or two. But Jerry assumed that just because the trend had persisted for as long as he could remember, things had always been like that. Of course, that was not the case. Looking over a longer period of time, the oil business has suffered numerous catastrophic meltdowns. But because he had never lived through one himself, Jerry didn’t even entertain the possibility that the time was ripe for another one.” In January 1986, 18 months after the meeting with Jerry, Global Marine had filed for bankruptcy.

A classic example of historical myopia. We assume the recent past is the most accurate predictor of the future and that the more distant past is much less relevant or important. Jerry pointed out that the energy sector moves in cycles, which is correct. But he failed to realize that some cycles are on a larger timeframe and take much, much longer to play out. These cycles, known as supercycles, run their course while engulfing the shorter cycles along the way.

The Doctrine of Elite Infallibility

“One of the primary causes of this unrealistic optimism in the corporate and investing worlds is an almost slavish faith in the capabilities of our country’s elite. People seem to think that a degree from a top university inoculates its holder from failure. I can’t tell you how many times stock analysts and fellow money managers have tried to convince me that a clearly troubled company would turn around simply because its CEO was a graduate of some distinguished school. “He’s a Harvard MBA,” they’ll say in almost reverential tones, as if that fact alone would be enough to offset overwhelming evidence that, despite their impressive backgrounds, they were running their businesses straight into the ground.”

“Self-delusion is a powerfully democratic force. You can be richer, smarter, and more successful than anyone else. But if you’re not brutally honest with yourself about your own potential for failure, you’re going to have a problem – and you’re going to lose money, maybe a lot of money.” - Scott Fearson

Other Examples & Mentions in Chapter 1

- California Coastal Communities (Stock Symbol: CALC)

- TCB - Texas Commerce Bank

- Lunch meeting with Ken Lay from Enron

- Was pitched an opportunity to invest in Bernie Madoff’s fund, and narrowly avoided that disaster

Dead Companies Walking: How A Hedge Fund Manager Finds Opportunity in Unexpected Places

Scott Fearon's insider's guide to profiting from failing companies and distressed investments. Learn how a successful hedge fund manager identifies businesses on the brink of collapse and turns market pessimism into investment opportunities. This contrarian approach reveals valuable insights for spotting corporate decline and capitalizing on market inefficiencies.

View on AmazonChapter 2: The Fallacy of Formulas

They relied too heavily on a formula for success.

The chapter 'The Fallacy of Formulas' warns about relying too much on formulas or financial models. Scott explains that just because a business strategy or a mathematical formula worked before, it doesn't mean it will always work.

While it's extremely important to research a company thoroughly, focusing only on numbers can make you miss other important information. Scott highlights the value of meeting with a company's management team to get a real sense of how the company is doing and what their strategy going forward will be.

Scott also describes his own experience of missing out on two of the best investments he could have made, Starbucks and Costco, because of a blind adherence to a formula. After meeting with the CFO’s of both companies in the early 90’s, his gut was telling him to buy both stocks. But because of the strong belief he had at the time in his GARP formula (growth at reasonable price) that showed that the stocks were over-valued at the current price, he decided both stocks weren’t at the right price to buy. - One of his biggest trading errors.

Other Examples & Mentions in Chapter 2

- Scott Fearson’s first short sale: TGI Fridays- Value investors got so obsessed with the cash flow numbers that they missed the reality of the company – growth was slowing.

- Value Merchants (VLMR) - A dollar store that had a formula of doubling store growth yearly, which ended up being the death of the company.

- Advanced Marketing Services (ADMS) - An example of how hard it is to spot a fraud. A legit company, but the fraud was perpetrated by a handful of employees in a single department doctoring accounting statements.

- Idearc (IAR) - A publicly traded Yellow Pages company with shrinking revenues and loaded with debt, was able to stay afloat many years longer than it should have because of the company’s EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization). Investors relied heavily on this formula and completely ignored that it was a quickly dying industry.

Chapter 3: A Minor Oversight - Your Customers

They misread or alienated their customers.

This chapter talks about the management teams that completely lose focus of who drives their revenue… their customers. They fixate on some given set of data or analysis instead of the most important data set of all: how people in the real world behave.

“Sometimes company managers get so emotionally attached to their creations, or so convinced that they’ve discovered a unique market need, that they wind up being the last people on Earth to realize that nobody else shares their opinion. Investors are also susceptible to this overconfidence. They buy into a company that they themselves patronize, or that they are convinced creates an indispensable product or service, and they often ignore very compelling evidence that the rest of the market does not share their tastes. It’s called confirmation bias – believing what you want to believe and discounting contrary information – and it has destroyed countless portfolios and businesses alike." ~ Scott Fearon

Examples & Mentions in Chapter 3

- JCPenney (JCP) - CEO, Ron Johnson, decided to eliminate coupons and started stocking more expensive brand name merchandise. The problem was that people who shopped at JCPenney Liked using coupons. His doomed upscale strategy shows the dangers of confusing your own tastes with the tastes of your customers. The CEO wanted to make JCPenney into a place where he and his friends would shop.

- First Team Sports (FTSP) - A seller of inline skates. “Shorting a company selling a fad product is a very tricky game. Even if you’re convinced that their popularity isn't going to last, you still can’t tell when it’s going to fade.” FTSP was trading at thirty times the company’s earnings when Scott first started shorting it.

- Chemtrak (CMTR) - Specialized in take-home medical tests. Chemtrak’s only product was an over-the-counter blood test for cholesterol levels, and it had just received FDA approval. Before shorting the stock, Scott did a minor investigation: “I sent a gofer who was working for me at the time to twenty drug-stores around my office. I had him put a small nick on the packaging of the first five Chemtrak tests on the shelf at every location. He went back every other week for several months. At the end of this process, those first five tests in all the stores still had nicks on them. Not a single one had sold. That was all the proof I needed. I shorted Chemtrak’s stock”.

Chapter 4: Madness & Manias

They fell victim to a mania.

Throughout this book, Scott Fearon talks about the popular manias that he lived through: The oil boom, the Dot Com mania of 2000, and the Housing Bubble of 2008. In this chapter he also talks about mini-manias, and manias that take hold of individual companies. Management and the investors start to believe in all the hype and happy parts of the company or product narrative and are blind to the gaping flaws in their reasoning.

In many ways, mania participants suffer from acute cases of historical myopia. They only look as far back as the first days of their particular bubble and assume that older ways of living or doing business have now been rendered permanently obsolete. Manias cause people to believe they are seeing the new normal.

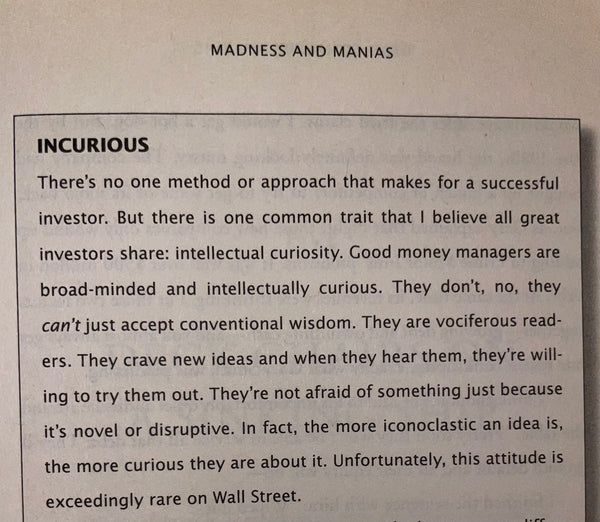

“Effective money managers do not go with the flow. They are loners, by and large. They’re not joiners; they’re skeptics, cynics even. Whatever label you want to put on them, the trait they all share is that they don’t automatically trust that what the majority of people – especially the experts – are doing is necessarily correct or wise. If anything, they move in the opposite direction of the majority, or they at least seek out their own course.” ~ Scott Fearon

Examples & Mentions in Chapter 4

- Cygnus Therapeutics (CYGN) - “One of the more maniacal industries in the last thirty years has been biotech. I’ve seen dozens of companies in that sector come public – and soar to huge valuations – on nothing more than a few promising results in the lab”. Cygnus had a product called GlucoWatch, a watch that could check the wearer’s glucose levels. Scott checked in on this company 5 times over an 8 year period, and each time he visited the executives told him “The watch is almost ready”. Only the reason for the delay changed. The hype around this one product kept the company up and raising money for many years before they went bankrupt.

- Shaman Pharmaceuticals (SHMN) - Shaman managed to get by on little other than blind faith. The company CEO planned on using plants and herbs from the Brazilian rainforest to create pharmaceutical grade drugs back in their labs. In over a decade, they never produced one revenue generating medicine. But the power of its story was enough to bring in hundreds of millions of dollars in public stock offerings and PIPE deals. The reason Shaman was able to survive so long and raise so much money without any results is that the CEO was great at telling a story that a lot of investors wanted to believe in. (Sounds like MULN & SHOT recently)

Chapter 5: Deck Chairs on a Sinking Ship

They failed to adapt to tectonic shifts in their industry.

Chapter 5 focuses on the companies that are in an industry that has fundamentally and permanently changed. Many leaders of these companies fail to make the changes required and instead just try to hold out because they can’t accept the unpleasant truth that their industry, and the rest of the world, has left them behind.

Some companies try to adapt to the tectonic shifts in their industry, and some try to cling to what worked for them in the past.

Examples & Mentions in Chapter 5

- Blockbuster (BBI) - Blockbuster revenues were way down, and they had over nine thousand brick and mortar stores with tens of thousands of employees. All while Netflix was coming up with web based movie rentals. Their solution: to add more candy, movie posters, and Hollywood memorabilia to their stores. Their next solution was to double down on the retail idea, they went for a merger with Hollywood Video and Circuit City in what was being called operational synergies. “Over the years, I have learned to watch out for the word synergies when two troubled businesses combine”.

- PageNet (PAGE) - in 1999, the CEO of PageNet spent hours trying to convince Scott that pagers will continue to be a profitable business even after everyone has a cellphone, because people would prefer to carry both a pager and a cellphone. The next morning, Scott shorted PAGE, and for good measure also shorted the only other publicly traded pager company.

Chapter 6: The Buck Stops… There

They were physically or emotionally removed from their companies’ operation.

This chapter highlights management that was just out of touch with their company or employees, and then trying to find someone or something else to blame for their lack of self-awareness. There’s a few examples of management that are just completely out of touch, or others that try to blame their failures on macro-economic reasons.

People don’t like to face bad news, especially when it means admitting that they’ve made stupid decisions. They invent all kinds of reasons and rationalizations to keep from owning up to their own mistakes.

“The Bible says, “Pride goeth before destruction.” I think they should put that quote in business textbooks, because pride often goeth before bankruptcy, too.” ~ Scott Fearon

Examples & Mentions in Chapter 6

- JCPenney’s - When JCPenney’s hired CEO Ron Johnson (famous hedge fund manager Bill Ackman was responsible for the hiring btw), he refused to move near the company’s headquarters in Texas, and stayed back in Silicon Valley. From there he would send out monthly video recordings from his mansion in the valley and required company employees to watch these videos. According to Scott, “You can’t make major changes in a company with thousands of employees unless you connect with them directly and earn their loyalty.”

- Consilium (CSIM) - After studying the numbers and seeing dangerously high debt and revenues flattening out, Scott went to visit the CFO. The CFO confidently claimed that sales are only down because the Fed has been constraining the monetary supply over the last few quarters. This could affect major companies, but a small software company with competitors that were not affected just didn’t add up. Scott immediately shorted the company at $17 and covered a year later at $10.

“A tried-and-true tradition on Wall Street: When things go wrong, investors and corporate executives alike love to blame that old boogeyman, short-sellers. It’s a convenient way to justify unwise investments and deflect attention from the real reason companies lose value: the poor decisions of the people running them. Instead of looking inward and redirecting a business strategy, this scapegoating allows leaders and shareholders the illusion of shedding their own responsibility for the condition of their firms.” ~ Scott Fearon

Chapter 7: Short to Long

In this chapter, Scott talks about how he actually makes a lot more money going long than he does short. He spends much more time looking for companies to invest in than he does scouting for dead companies walking. There are also a few companies that he was short in but the company turned around their economic future and Scott ended up covering his position and actually going long. He talks about how nowadays there are just more and better opportunities on the long side. Partially because of SEC rules and regulations to get listed, but mainly because there are so many amazing short-biased hedge funds and money managers now compared to back in the 80’s and 90’s.

“The key is flexibility. I try not to have a rigid view of things. I assess the numbers, I meet with management teams, and I do my best to make the correct call on a given stock, whether that means shorting it, buying it, or holding off. Sometimes I hit a home run. Sometimes I lose. But I always do everything I can to stay open-minded and willing to adapt to new information or circumstances.” ~ Scott Fearon

Examples & Mentions in Chapter 7

- Cost Plus World Market (CPWM) - This is a retail company that started out by selling strange and random items from all over the world. Scott described it as a “treasure hunt retailer” and loved to go with his father as a kid. New management changed their whole business plan to cater to higher end customers and this caused the company to almost completely go out of business. A new CEO came in right before bankruptcy and went back to their original “treasure hunt retail” strategy and was able to make the company successful again. Scott also mentions how the Cost Plus management team was able to commit 4 of the 6 business sins that he looks for in dead companies walking.

“I made about $1 million shorting its stock. That’s not a bad return. But when I bought the same amount of stock as I had shorted (225,000 shares), I netted more than $3 million in just over a year. That’s triple the money in a third the time… You just don’t make that kind of money on shorts. There’s a fixed number between a stock price and zero, and that’s as much as you’re going to get out of those positions. For long investments, however, there is no such limit.” ~ Scott Fearon

- Zales Diamond Store (ZLC)

- International Gaming Technology (IGT) - Creators of the progressive jackpot slot machines.

Questions & Comments:

How did Scott Fearon set up the meetings with CEO’s or CFO’s?

When talking about the company Texas Air, Scott talks about how he saw an opportunity in investing in the company, so he looked up the phone number for Texas Air’s offices. He called, and asked the receptionist if he could talk to the company’s Director of Investing Relations, who was not available. An hour later he got a call back from Frank Lorenzo, CEO and corporate world legend.

On Acquisitions

Scott Fearon explains his take on acquisitions: In many cases, acquisitions can be successful if carefully conducted. Some acquisitions will increase revenue without increasing debt. But many acquisitions tend to be crapshoots when used as a means for growth.

“No matter how many lawyers and auditors an acquiring company hires, no matter how much due diligence it performs beforehand, the seller almost always gets a better deal than the buyer. Sellers know where the bodies are buried in their businesses, and there’s usually a good reason why they’re willing to give up ownership.” ~ Scott Fearon

Dead Companies Walking was a pretty cool book. I love hearing Hedge Fund managers explain their process. Scott Fearon has a lot of interesting little stories in this book that I didn't have time to cover in this summary. Also, the last 2 chapters he changes the pace and talks about investing and the ways he recommends to invest. There's a lot of useful information in those last 2 chapters for everybody, and I think those last chapters alone are enough of a reason for anybody to read this book.

Here's a cool short interview I found of Scott Fearon explaining his process:

If anyone has any book recommendations, hit me up anytime on Twitter / X or leave a message here.

Here's another similar book I covered a few weeks ago that I would recommend checking out:

1 comment

I’m reading this book at the moment.

Kriminil , really sick website man! :)

Laza_Plavi

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.